|

If you are sanctioned for failing to meet an “expectation”, it is, in fact, a “condition”. For a long time I have been interested in why deprivation and poverty are associated not just with academic outcomes, but with behavioural outcomes, and on my journey to understand this I came across a researcher called Sendhil Mullainathan and his work on the concept of scarcity. In his view, scarcity is a much more wide-ranging concept than poverty (an arbitrary threshold of income), i.e. we can have a scarcity of time, health, family support, relationships, cultural input, etc. - all of which can impact our outcomes. In describing the impact of scarcity he uses the analogy of packing into a smaller suitcase, and inspired by the #IncludEd2023 conference today, I’d like to start with this. Two pupils are going away for a week, one packing into a large suitcase and one into a smaller suitcase. The suitcases can be seen as strict metaphors for disposable income (family income in this example), or in a broader way as availability of lots of different resources… but they both articulate a difference in experience. The pupil with a smaller suitcase (i.e. scarcer resources) has a smaller capacity for items, therefore…

Could you list all the conditions / expectations children must meet to engage fully in your school? When we put pressure on parents/carers to immediately provide a new pair of school shoes, do we consider the scarcity that so many are living with? Less time because of childcare or multiple jobs, the cost and time of travel to get the shoes, the cost of the shoes, and what is the “or”? What isn’t being bought, what isn’t time being invested into?

Living in scarcity means a “lack of slack” for mistakes - we all make mistakes but they don’t cost us or impact us all equally. There is very little flexibility for this within most school behaviour systems as the consequences appear superficially the same - the same detention time is given. The actual impact - socially, emotionally, educationally - may vary widely.

What prompted me to write about this today was hearing from two speakers who have experienced the care system. Consider the conditions we place on children in school, then consider the size of the suitcase a child in care is packing, i.e. the multiple levels of scarcity they may be experiencing. We have conditions on appearance and equipment - coat, black socks, bag, colour of pen, PE kit, pencil-case, etc. We have conditions on behaviour - a consistent requirement to accept adult authority and direction, regulate level of activity, attention, and emotional response. Even peers come with conditions for integration - they could be clothing, games consoles, cultural references, a similar capacity to spend time together outside of school. Some of these may feel impossible for a young person to achieve… Lemn Sissay OBE described it so viscerally today when he recalled “the smell of people with families”. The speaker before Lemn was Jade Barnett, which is a name you will come across again in the future. Her educational journey travelled via two managed moves, a pupil referral unit, a move into care then a move into a care home at the opposite end of the country. Jade is a model of the most positive outcomes - today she held five hundred minds in her hand purely because she speaks with such intelligence, articulacy and power. But, as a child, she was forced into a situation where she was packing into a small suitcase. And the schooling system places yet more conditions on her, and others like her. Nowhere in her speech did she imply that those conditions were helpful; where many, such as Lemn, feel like they don’t belong already, the consequences of failure to meet these “expectations”/conditions must only reinforce that perception. At their least useful, they make engagement and access to education harder for some of the most vulnerable. To return to more typical language of schooling, high expectations can no longer be a cover for just describing a very large number of conditions. And we need to stop painting such conditions as supportive to young people by their mere presence. That is to confuse equality of expectations/conditions with equity, but that isn’t equity at all. In reality, we may be both ignoring the smaller suitcase and expecting more of the child who is packing it. Kat Stern

0 Comments

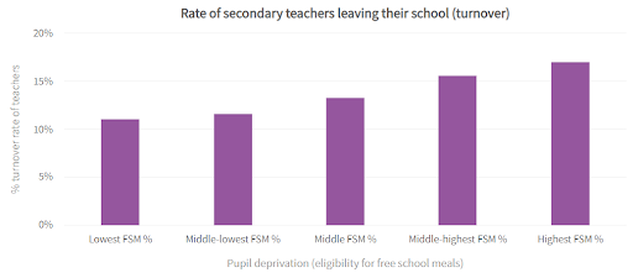

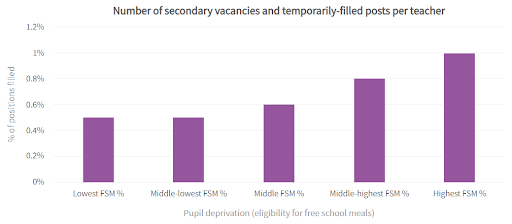

Free school meals and teacher turnover The recent publication of the new data dashboard from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) sheds further light on teacher retention and attrition issues; an issue which, as the sector is painfully aware, continues to move in an unfavourable direction. The data has been organised by geography (including by local authority), main teaching subject, and free school meal eligibility; the last of which has demonstrated some striking correlations. The data has been organised into quintiles (fifths) by the proportion of pupils in each school who are eligible for free school meals (FSM). The following findings in particular display the challenging context that some school leaders and MATs are facing:

Not only does higher turnover have the potential to negatively impact the learning experience of students (see Second Time's the Charm? How Sustained Relationships from Repeat Student-Teacher Matches Build Academic and Behavioral Skills (edworkingpapers.com) for an interesting paper on “looping”, i.e. having the same teacher for more than one year), but there are associated costs, such as advertising and recruitment. There are also broader pastoral issues to consider, such as relationships with students, parents and carers, and the local community.

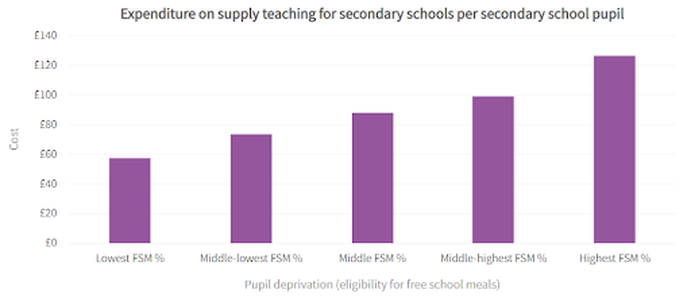

A high turnover of staff is exacerbated when recruitment is harder and schools may have to rely on temporary contracts. This is a problem typically associated with smaller, rural settings, particularly the most isolated. However, it also appears to be affected by the amount of deprivation within the cohort; and all of this leads to a hidden cost which is very pronounced…

The costings for the year shown above (2020) are as follows: from left to right £58, £74, £88, £99 and £127 per pupil.

That is a difference of £69 per pupil between the lowest and highest quintiles; a gap which is larger than the entire cost per head of the lowest quintile. Many leaders and trustees may be aware of the high costs that schools are spending on supply teaching; perhaps not as many are aware of the link to the deprivation level of their cohort. This blog started with a simple set of data which shows that teacher turnover rates are not evenly distributed across schools. As a sector, we need to recognise this fact, and consider the motivations that may underpin the patterns. It should also be considered at a national level, particularly in terms of funding. In terms of motivation, my initial response would be that higher levels of deprivation result in more challenging behaviour, as measured by suspensions and exclusions across our system. Such behaviours increase workload and stress for staff working in such settings, making supportive leadership, policies and processes even more vital for staff retention. Additionally, my own teaching experience tells me that the most vulnerable students need the most stable and caring relationships; something which may be harder to foster with temporary teachers and higher turnover. Unfortunately, it feels like a situation in which ground can be lost. School leaders and managers may want to continue their focus on staff support by prioritising wellbeing and focusing on the creation and implementation of systems that enable them and their learners to thrive. Where staff feel valued and able to manage a healthy work-life balance, they are more likely to work positively and collaboratively over a longer period toward the vision of the school leadership - and to stay long term in the profession. Kat Stern Link to the dashboard: Explore by school type - NFER

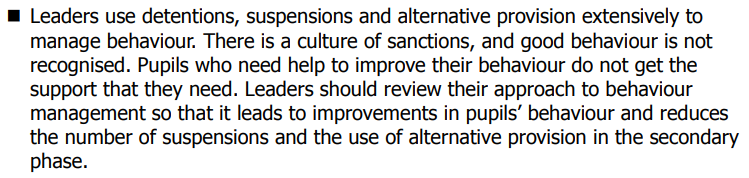

The article in the link above describes how one of England's largest multi-academy trusts may be stripped of one of its schools because of significant issues with behaviour and a lack of pupil support for key groups. The termination notice is damning and raises a large number of concerns, however the purpose of this post is not to draw more attention to this particular school. I want to focus in on one specific concern that was raised: that pupil suspensions are too high.

From the recent Ofsted inspection that prompted the termination notice:

This begs the obvious question... how high is too high? As a school leader, at what point should you be concerned that you have generated a "culture of sanctions"? What level of suspensions would be notable to an Ofsted inspector and what weighting would that have on your school's overall judgement?

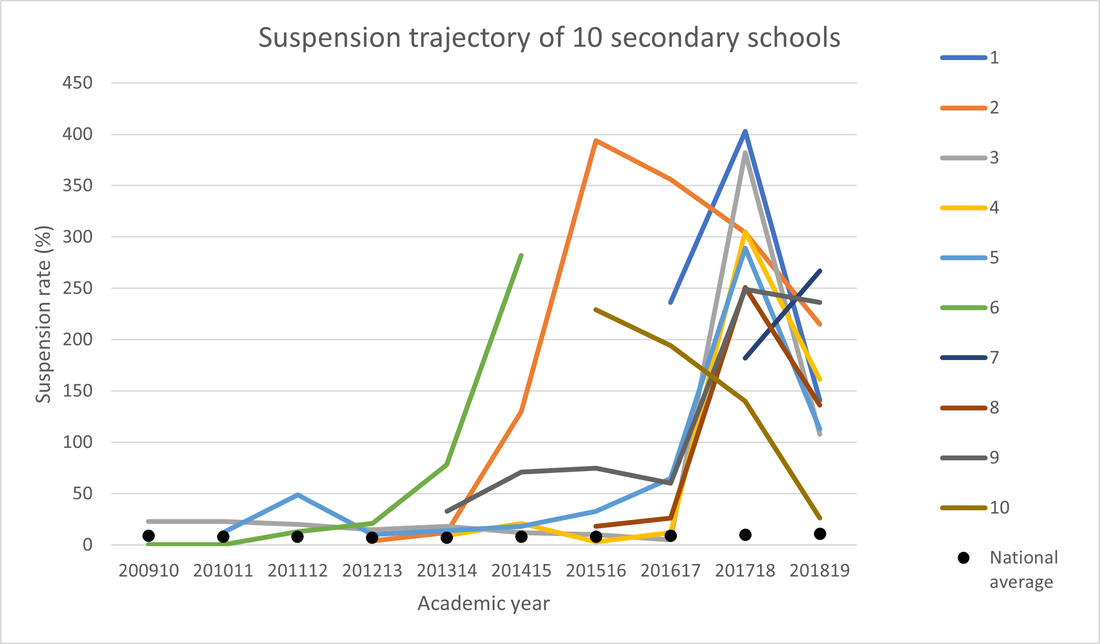

For data purposes we calculate the suspension rate of each school - a small school of 100 students who gave 5 suspensions in that year would have a rate of 5%, whereas a larger school of 1000 students with 40 suspensions would have a rate of 4%. The most recent set of exclusion statistics that the DfE have published relates to 2019/20 so there is no way for those of us outside of this particular school to know how high their suspension rate has been recently. The last data we have is for 2019/20 and their suspension rate was under 5%, so we have to assume there has been a large increase. But it is possible to shed some light on how high suspension rates in our state-funded schools can be. Take a look at the following graph which shows 10 such secondary schools, chosen for their particularly high rates. The small black marker indicates the suspension rate for English secondary schools that year, i.e. the national average. All are mainstream schools.

The first thing you can clearly see is that suspension rates can LEAP from one year to the next. Take, for example, school 3, which soared from a rate of 4% to 382% in 2017/18. There were 506 pupils and 1933 suspensions that year.

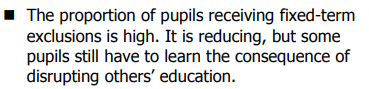

As you can see, this is not the highest suspension rate in this time period, as school 1 had 468 pupils in 2017/18 and gave 1886 suspensions. Their suspension rate was over 400% - surely this would fall into the category of a "culture of sanctions"? Which brings me to the title of the blog post - how important are these rates to Ofsted? Having looked at some of the reports for these schools, I can tell you that whilst the suspension rates were commented on, nowhere have I yet seen any reference to a "culture of sanction" or language that would convey a similar description. Below is a comment from the summary of an Ofsted report of school 2:

During the year of this inspection, school 2 had a suspension rate of 355%. Perhaps the majority of these suspensions occurred after the inspection, but this is extremely unlikely as it occurred in May. And the previous year's data was available... a rate of 393%. The overall school judgement was "Good".

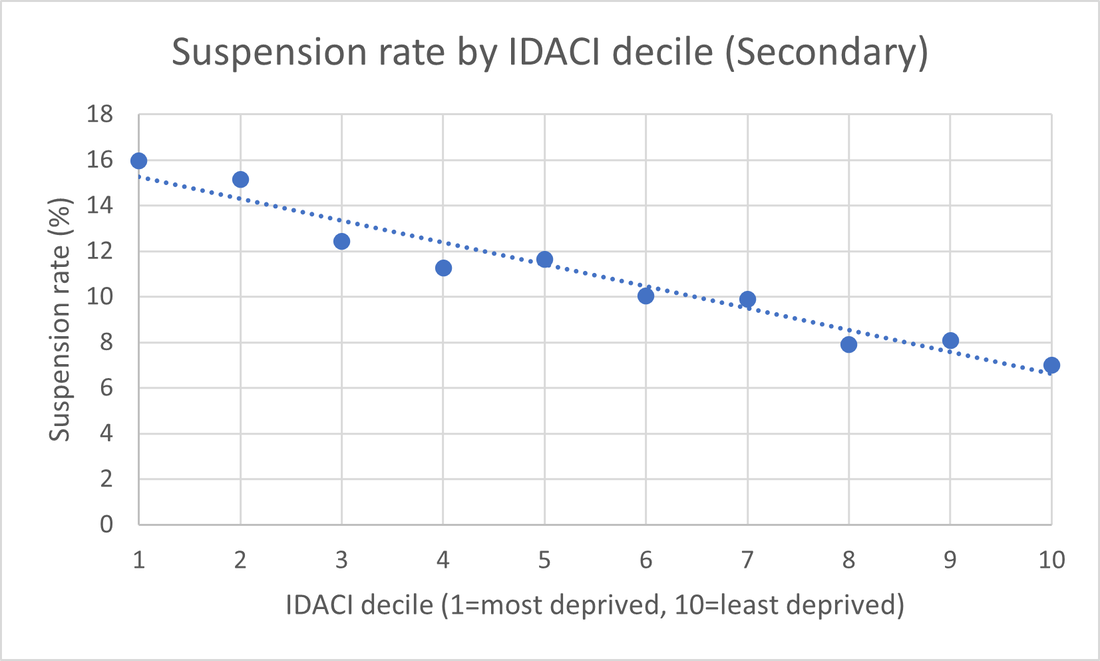

Despite these rates being amongst the highest of all state-funded mainstream secondary schools over a decade, they can be incorporated into the narrative of a "Good" school. High suspension rates alone do not appear to trigger an Ofsted inspection (or if they are supposed to then a couple of schools on this graph have slipped through the net). School 7 was not inspected until November 2021 despite having consecutive rates of 182% and 266%. School 10 was not inspected until January 2018. All of this makes it hard to understand Ofsted's interpretation of suspension rates and their importance; or whether there is an official position that may not be applied very equally (clearly 10 schools is an extremely small sample size). Are the number of suspensions and exclusions alone EVER a significant concern to Ofsted, or do they only become significant when combined with other issues? Looking at the data above, do Ofsted just not care that much about suspensions? The termination notice in the original article about Ark Kings Academy included the following quote: "Both detentions and suspensions are used very frequently, and leaders cannot demonstrate the impact of these strategies." The vast majority of educators (including myself) support the use of suspensions for serious breaches of the behaviour policy, yet suspensions are not a cure in themselves. As can be seen above, you can suspend the equivalent of every single child in your school three times in a year... and apparently still "need" to do it again the next year. Rates as high as these will always fall over time as they are so far above the mean, but even such exceptionally high rates of suspension clearly do not transform the behaviour within a school. I believe this is important for all of us to understand. If Ofsted are expecting an immediate impact of frequent suspensions (as could be implied by the quote above), perhaps the 10 schools in the graph above might make them think again. Many, many commentators, including Ofsted themselves, have emphasised the importance of behaviour in schools. There are urgent concerns about the negative outcomes associated with permanent exclusion; indeed I wrote a whole book on the demographics of excluded children and why some antisocial behaviours might occur. Suspensions disproportionately affect students who receive free school meals, students with special educational needs, and certain ethnic groups such as Gypsy/Roma pupils. For example, take a look at the graph below, which plots average school suspension rates for ten "blocks" of income deprivation (calculated by IDACI rank for 2018/19). You will see that higher suspension levels are associated with areas of higher deprivation.

In my opinion, suspensions matter. They matter to pupils, they matter to schools, they matter to families, and they are disproportionately associated with some of the most vulnerable students in our school system. They could be a useful marker of schools that need more support rather than more judgement. I guess I'm just not entirely clear how much they matter to Ofsted.

[I have tried to use as little information as reasonable so that schools are not easily identifiable (although all of this data is in the public domain).] |

|

Privacy policy

This privacy policy sets out how Expecto Patronum Consultancy uses and protects your information.

1. Collection of information

1.1 Data can be collected and processed during your visit to this website. The following are ways in which this may be collected:

(a) Data regarding your visit(s) to this website and any resources used, which may include but is not limited to: location data, traffic data, and any other communication information.

(b) Data contained in any forms you fill out on our website.

(c) Data collected when you communicate with our staff or our website. Any request you make via our website or to our personnel allows us to use information you have provided us with, relating to the products or services related to EP Consultancy.

1.2 Any data shared online is not completely secure and Expecto Patronum Consultancy cannot guarantee full protection or security, only that we will take all reasonable action to protect information that is shared with us electronically. Sharing such data is at your own risk. Where your information relates to services provided by Expecto Patronum Consultancy, it will be kept for a period of up to five years after your account is closed.

1.3 As per the Data Protection Act 1998, you have access to any of your data or information that we hold in relation to you. If you wish for this information to be released to you, there is a £5.00 administration fee prior to the data release. Please use the email address listed on the website if you wish to request your data.

2. Sharing information

2.1 Expecto Patronum Consultancy will not sell, rent, or share your personal data with any third party for marketing purposes.

3. Marketing Communications

3.1 Expecto Patronum Consultancy may send information regarding products or services that you may be interested in.

3.2 Should you not wish to receive these, an unsubscribe option is attached to these communications, which will prevent you receiving further information regarding products and services. We may still need to contact you for other operational purposes.

4. Third parties

4.1 Where third party links are present on the site, they are responsible for their own privacy policy. Expecto Patronum Consultancy is not responsible for the content or privacy of third party links.

This privacy policy sets out how Expecto Patronum Consultancy uses and protects your information.

1. Collection of information

1.1 Data can be collected and processed during your visit to this website. The following are ways in which this may be collected:

(a) Data regarding your visit(s) to this website and any resources used, which may include but is not limited to: location data, traffic data, and any other communication information.

(b) Data contained in any forms you fill out on our website.

(c) Data collected when you communicate with our staff or our website. Any request you make via our website or to our personnel allows us to use information you have provided us with, relating to the products or services related to EP Consultancy.

1.2 Any data shared online is not completely secure and Expecto Patronum Consultancy cannot guarantee full protection or security, only that we will take all reasonable action to protect information that is shared with us electronically. Sharing such data is at your own risk. Where your information relates to services provided by Expecto Patronum Consultancy, it will be kept for a period of up to five years after your account is closed.

1.3 As per the Data Protection Act 1998, you have access to any of your data or information that we hold in relation to you. If you wish for this information to be released to you, there is a £5.00 administration fee prior to the data release. Please use the email address listed on the website if you wish to request your data.

2. Sharing information

2.1 Expecto Patronum Consultancy will not sell, rent, or share your personal data with any third party for marketing purposes.

3. Marketing Communications

3.1 Expecto Patronum Consultancy may send information regarding products or services that you may be interested in.

3.2 Should you not wish to receive these, an unsubscribe option is attached to these communications, which will prevent you receiving further information regarding products and services. We may still need to contact you for other operational purposes.

4. Third parties

4.1 Where third party links are present on the site, they are responsible for their own privacy policy. Expecto Patronum Consultancy is not responsible for the content or privacy of third party links.

Proudly powered by Weebly